“At fifty, everyone has the face he deserves,” said George Orwell.

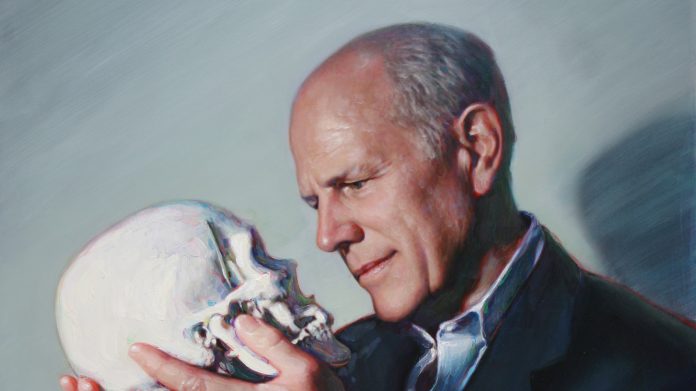

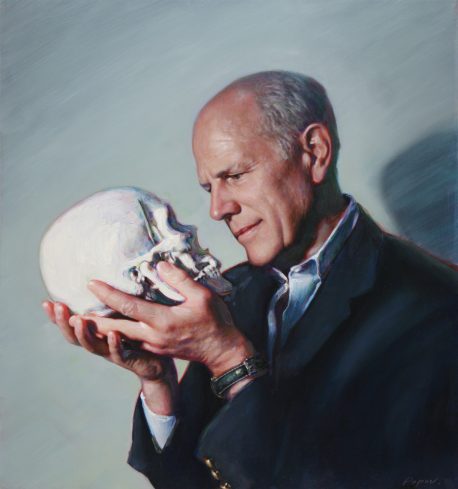

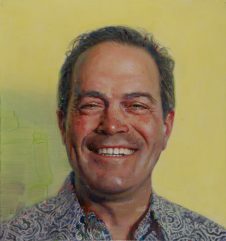

“Uh-oh,” thought Barnaby Conrad III, author of Absinthe: History In A Bottle and 10 other books.” I was almost sixty when Bay Area artist Valentin Popov said he wanted to paint my portrait. What would he reveal?”

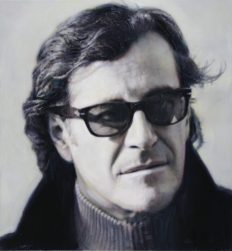

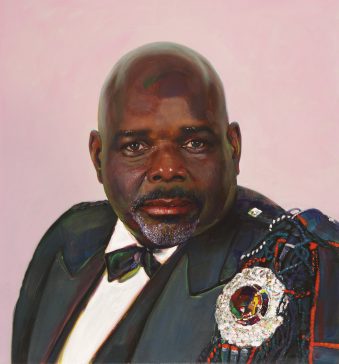

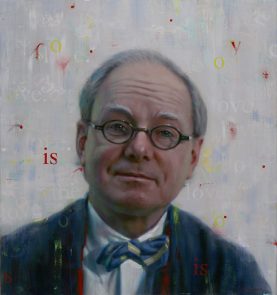

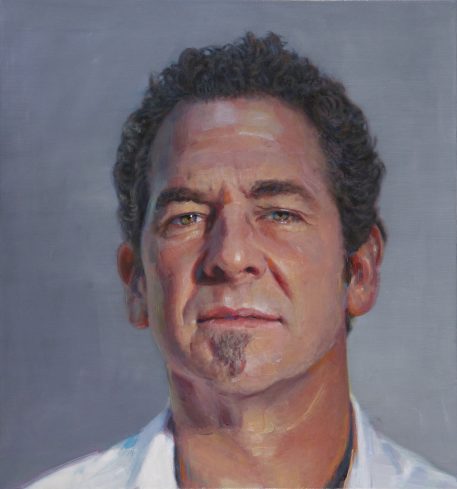

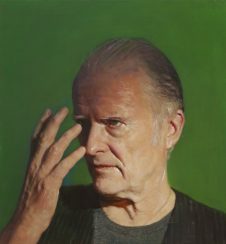

During the last three years Popov, a Ukrainian born, classically-trained artist, has produced over sixty portraits. His subjects include writers, artists, scientists, actors, software programmers, filmmakers, even a former CIA case officer. The Moscow-trained artist’s plan is to paint one hundred likenesses, each 28″ x 26” oil on canvas.

“My goal in every portrait is to reveal the humanity of the subject to the sympathetic viewer,” says Popov.

It was a sunny day when Popov mounted the stairs to Conrad’s eighth-floor writing studio in San Francisco. Cup of tea in hand, Popov wandered around the cluttered workspace inquiring about various objects: the stuffed head of an antelope, an old typewriter that belonged to columnist Herb Caen, a penguin-shaped cocktail shaker, fishing rods leaning in a corner, and a mounted amberjack from the Gulf Stream .

Then Popov spotted a human skull sitting on a cluttered table. “May I?” he asked, before picking up the skull. The skull’s jaw was hinged with a metal spring. While gently opening and closing the mandible, he asked Conrad why he owned a classic prop of a medieval philosopher. “Vanitas vanitatem,” said the author. “Reminds me of the fragility of life. I broke my jaw 25 years ago while jogging in Paris. You don’t want to hear about it.”

But that was precisely the story that Popov wanted to hear. And as the author contemplated the skull and recounted the story, Popov photographed him. Within two weeks Popov painted a very modern Hamlet-esque portrait of Conrad, with a nod to Warhol.

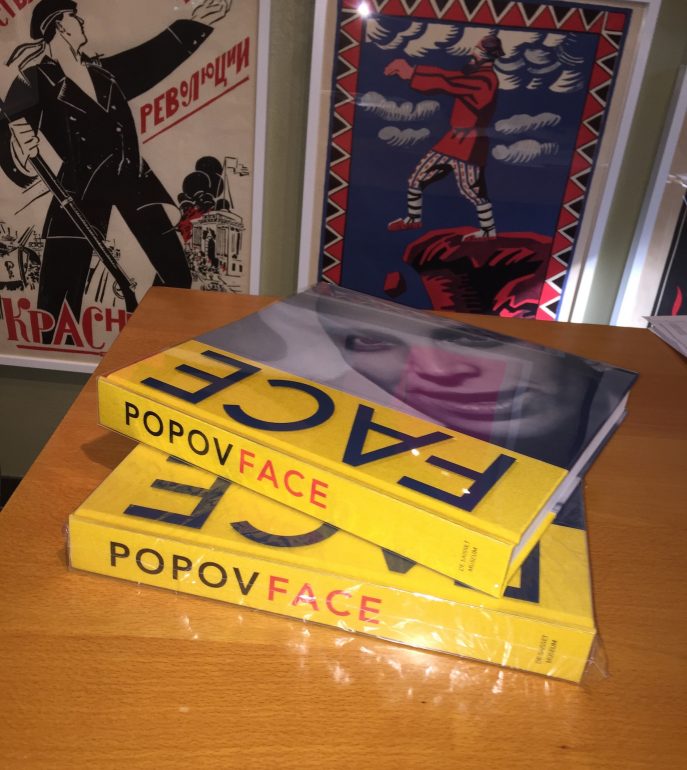

Popov’s portrait series pays homage to Andy Warhol’s dream of a big show in which he would cover the walls with the images of all of the famous—and infamous—faces he painted. For Warhol, that particular show never happened. For Popov, the project will not only cover museum walls, but also coffee tables — in a large-format art book —displaying all the portraits painted in the course of his career.

What makes a good portrait?

“Every portrait that is painted with feeling is a portrait of the artist, not the sitter,” said Oscar Wilde. A great portrait artist has two goals: achieving a good likeness, and making an interesting work of art. Years from now, the owner of a portrait of a long-dead ancestor will care less about the likeness than the overall aesthetic strength of the painting.

According to author and former museum curator Robert Flynn Johnson, Popov is one of the few contemporary portrait painters to watch. “Through the brush of this master comes the essence of personality. The energy and freshness of Popov’s portraiture transcend the dull predictability of photographic likeness or mere stylishness.”

Johnson observes,“Portraiture is the only area of art where there is active interference with the creative process by the subjects of that art. For a portrait to be truly original and to catch the essence of the sitter, the artist must be free to control the outcome. It takes a sitter who is confident, curious and brave enough to submit to Popov’s intriguing and unpredictable collaboration.” When this occurs, extraordinary depiction can occur. He cites a few examples: Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Egon Schiele, Max Beckmann, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, David Hockney and Chuck Close.

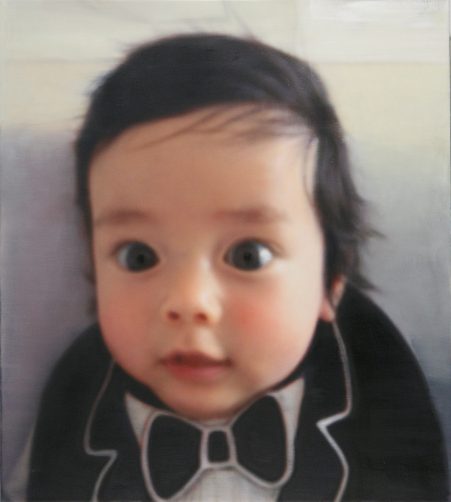

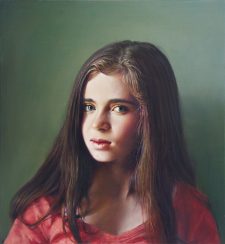

Conrad was so pleased with the results of his portrait with the skull that he commissioned Popov to paint his infant son Jack clutching a monstrous carved Halloween pumpkin. After finishing the portrait, Popov added a thought bubble above the boy’s head with the Russian words for “I love you.”

Says Popov, “I paint people. Humanity may be disappointing at times, but it’s all we’ve got on this planet, and painting is a way to reveal who we really are.”

To meet Valentin Popov and learn more about his project, watch FACE, a short documentary by Celik Kayalar.